By Kevin Barrett, for Al-Andalus Tribune

It is said that by the invocation of God (dhikru ‘Lláh) a believer attains such peace of soul that the great terror on Resurrection Day cannot sadden him; how then could he be disturbed by whatever trials and misfortunes may befall him in this world? So be constant in the invocation of your Lord, my brother, as we have advised you, and you will see marvels; may God fill us to overflowing with His grace. -Shaykh Al-`Arabi ad-Darqáwi, translated in Letters of a Sufi Master by Titus Burckhardt

We are witnessing the ugliest spectacle in human history as the first-ever live-streamed genocide, filmed in real time by its victims, reaches its crescendo. The Antichrist occupying Palestine is the avatar of ugly. Horrendous images—starving children, high-rise apartment buildings exploding, Charlie Kirk’s throat spurting blood—slam into our eyeballs with the rapidity of machine gun fire.

But God has put us here to witness this, and everything else. There is glory in sumud, “steadfast perseverance.” Complete surrender to God (islam) involves both the fulfillment of the prayer “let me be pleased with what pleases You” and the patient persistence—“persist in (pursuit of) Truth, and persist in patient striving”—mentioned in the Qur’an.

People in Yemen, Iran, Lebanon, and Palestine have done the right thing, the beautiful thing, by taking up arms and fighting Antichrist. Here in Morocco…not so much. But the glorious patience and persistence of the Resistance is at least faintly echoed here by the Maghreb Sumud Flotilla, which is sailing to Palestine with the Global Sumud Flotilla.

The sight of a huge fleet of small boats setting off to deliver food and medicine to Gaza, sails billowing in the Mediterranean breeze, is heartrendingly beautiful. The concept of a Maghreb fleet, bringing together North Africans from several unnecessarily-divided nations—and uniting Muslims and Christians—is in itself sublime.

My recent article “Chefchaouen and the Beauty of Defensive Jihad” invokes beauty jihad: striving against spiritual ugliness, both in ourselves (greater beauty jihad) and in the world around us (lesser beauty jihad). The word jihad itself means “effort, struggle, striving” in the path of God, and the artist’s effort to find or make beauty in and from the world we witness amounts to a kind of heroism.

Can Beauty Save the World?

Alex Krainer recently offered the provocative headline “How beauty could save the world.” His article discusses Chinese social media videos documenting beautiful craftsmanship. Projects include traditional bamboo furniture, water wheels, andteapots.

Krainer, an economist and investment advisor, asks:

“What if, instead of industrial hyperproduction we made craftsmanship great again? We’d produce less stuff, but the stuff would be more valuable, more beautiful and more durable.”

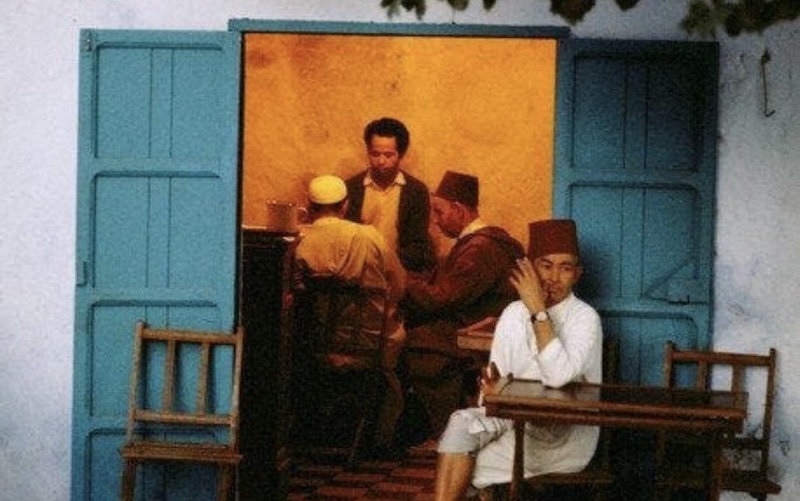

If there is ever a global “beauty jihad” to make craftsmanship great again, it could, like the Almoravid and Almohad movements, come surging out of Morocco, where great craftsmanship never went away. The Moroccan landscape of partially-forested mountains, variegated seashores, and sun-blazed deserts offers a spectacular backdrop for a “traditional beauty industry” of woodwork, leather, ceramics, metalwork, and weaving—as well as inspiration for painters, photographers, sculptors, writers, musicians and other fine artists.

Unlike in so many other countries regionally and worldwide, where traditional craftsmanship was largely killed off by colonialism and industrialization and had to be artificially resurrected to promote tourism, Morocco has an unbroken heritage of handicraft dating back centuries or in some cases millennia. The French colonization here lasted only around four decades, as opposed to 150 years in neighboring Algeria, and was much less heavy-handed, allowing traditional Moroccan religious and esthetic life to maintain a certain continuity.

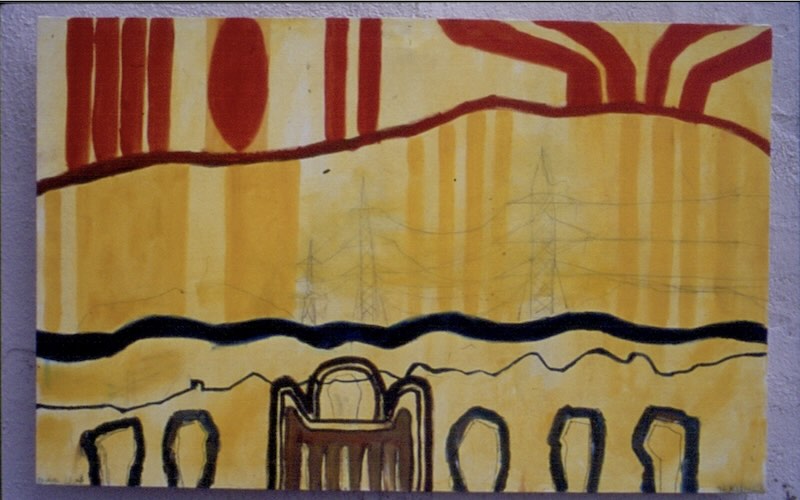

I bracket “religious and esthetic life” together because they are two sides of the same proverbial coin. The so-called arabesque designs of Zellige tilework, stucco carving, and woodwork are not frustrated attempts at individual artistic expression constrained by a religious ban on representation, as ignorant partisans of Western art sometimes claim. Nor are the so-called Islamic geometric principles that underly them mere academic exercises. They are reflections of spiritual beauty actually witnessed by those who succeed in the great undertaking of islam, ecstatic self-surrender to God. And they are incentives and encouragement to others pursuing that same undertaking—an aid to the contemplative life, and a glorious vision of its eventual fulfillment.

Morocco has succeeded in preserving these traditions of spirituality and beauty, even as they eroded elsewhere, for various reasons—a strong guild-based apprenticeship system, financial and other support from the monarchy, specialized schools like the École des Métiers d’Artisanat in Fes, the development of cooperatives and fair trade movements, and of course the national pride of a country that traces its political-cultural identity all the way back to the founding of the Idrissid dynasty in 788 (and to the even earlier emergence of Islamic al-Andalus, with which Morocco has always been inextricably intertwined). But as I mentioned earlier, what saved all of this heritage was the relatively light footprint of the destructive, nihilistic Euro-American imperialism and colonialism that has laid waste to traditional civilizations elsewhere.

In neighboring Algeria, brutally colonized from 1830 to 1962, French authorities dismantled artisanal guilds, mass-imported industrial goods, marginalized traditional crafts, and waged a cultural war against Islam and the Arabic language. French colonization of Lebanon and Syria, while not quite as extreme, yielded similar results. All of those countries suffered horrendous destruction from imperialist-colonialist-imposed wars. Most of the anti-imperialist forces that emerged were leftist-modernist in orientation, indifferent if not hostile to traditional Islamic lifeways and associated esthetic traditions. That same syndrome affected Egypt and Iraq, which like Syria were once thriving centers of traditional Islamic civilization. As for the Gulf States, their traditional lifeways were destroyed by American neocolonialism and oil wealth—a story beautifully told in Abdelrahman Munif’s Cities of Salt novels.

Nowhere, of course, has the colonialist assault on an indigenous Arab-Islamic people been as obscenely ugly as the Zionist Antichrist’s assault on the Holy Land of Palestine. What the Zionists have done to Gaza will never be forgotten, nor forgiven, even until the day the rocks and trees cry out for justice.

Morocco, at least partially preserved from the destruction visited on neighboring lands, contains the seed of the new al-Andalus that could sprout from the ruins of nihilistic Euro-American modernity, transforming the barren landscape of the modern world into a latticework of beautiful organic and geometric forms—a built environment that resonates with the peaceful soul, al-nafs al-mutmainna, and serves as a dignified abode and stimulus for the contemplative life.